We have sent the Kenya Defence Forces this week to help stabilise Africa’s giant, the

Democratic Republic of Congo, our newest member of the East African Community. This

action illustrates that French-speaking Africans are no longer our neighbours but kinsmen in

a region stretching from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic.

With deepening ties with the land formerly called Zaire, Kenyans will be exposed to more

than Lingala rumba and vivacious Kitenge fabrics they know since the Mobutu era. Literary,

music and art trends from Congo will present new inspiration opportunities to Nairobi,

Kampala and Dar es Salaam. Translation studies and Francophilia may soar among our youth

and creatives, it is hoped. Cultural exchanges thrive where distant markets connected are.

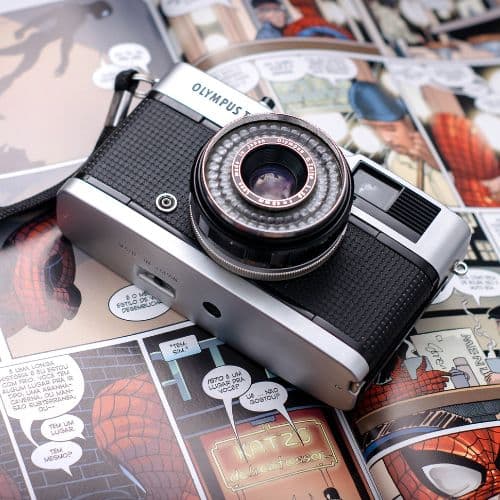

Take the example of a genre that is larger than life in Kinshasa: graphic novels. These are

books that tell stories through the media of comics: animation series in print form. Eleven

years ago, BBC carried an interesting story by Thomas Hubert reporting from Kinshasa. It

was titled: Capturing Kinshasa through Comics.

The English-speaking world became aware of an exciting Congolese writer called Papa

Mfumu’eto Premier. Pundits agree he is one of the most influential comic authors in

Kinshasa and francophone Africa. Premier lives successfully in Congo out of his widely

popular graphic novels, such as The Python that Ate a Woman in Kinshasa.

In his interview with Hubert, the writer said his aesthetics originate from unique African

spiritual worldviews. Premier said he specialises in mystic-religious-secret comics because

he wants to take his art to realms beyond human understanding. Many other younger

writers interested in graphic design, literature and animation exist courtesy of the

refreshing insights into African literary heritage instigated by the likes of Premier.

Out there in the West, graphic novels are a big-time genre. I was introduced to them by an

artist friend of mine in Berlin. She has both German and Jewish roots. She was fascinated

with a haunting story I told her about my maternal grandfather Wanjohi, who went to

Abyssinia (Ethiopia) and Burma (Myanmar) in World War II as part of the King’s African

Rifles.

The Holocaust, the mass killing of the Jews of Europe in the same war, brought us together

in the oddest of ways. We were two people worlds apart brought across the divides of

cultures by one of the most destructive episodes in human history. I was in Germany for my

further studies in literature back then.

For my 30th birthday, she introduced me to this unique literary form by giving me, one

summer day, a red-jacketed book called Maus. It is on my ebony intellectual office shelf

even today, a lingering memento from the land of ideas.

Maus was penned by Art Spiegelman, an American Jew, out of his haunting family history

after interviewing his father, a Holocaust survivor originally from Poland. The book was

serialised widely in the 1980s.

The graphic novel merges words and images. It combines the power of language and

imagination. The series of animated characters and their actions follow the typical storylines

of the world. A conflict is introduced, climaxed and resolved in the end by action-packed

accounts. Dialogue and character development are crucial elements in this art, as is

illustration.

Several sub-genres exist in this type of novel. Some like Premier from Congo write ones

based on superhero characters akin to those on TV programmes and DVDs popular with

Kenyan kids today. Some like Spiegelman type types out of family or communal narratives.

You can think, therefore, of heroic graphic novels and communal/personal graphic novels.

Graphic novels appeal quite nicely to the youth, who can identify with this mode of

storytelling from their modern living rooms and childhood media experiences. Gone are the

three-stone firesides and nonagenarian grannies with granaries of folktales.

African tales and tale-making cultures have taken several new turns. The electronic media

and digital media are the new dimensions of African storytelling. In print, it is the comic and

the graphic novel that relate this newness of African literatures.

Visual literacy and verbal literacy should be developed hand in hand in this era of

competency-based education. Teachers of literature at all levels of learning in Kenya should

consider the wonderful chances that exist in graphic novels' storytelling heritage. The more

diverse the range, the better, and as we perpetuate tales of old, let us relent not in

exploiting the new.

The Tintin, Spiderman and Ben Ten generations are alive and well in Kenya and across Africa

today. Local artists and literati should embrace them and their unique readerly habits and

appetites. One way to do so is to embrace the graphic novel culture of Kinshasa and spread

it across the counties of Kenya.

Other African countries with a strong presence of the graphic novel exist. Zimbabwe is a

good example. Eugene Mapondera has created Kwezi, a Zimbabwean bounty hunteress who

battles crooked politicians in her Umzingeli series. Bill Musuku is without a doubt the most

successful Zimbabwean graphic novelist. His series revolve around Razor Man, a small-time

mechanic by the day, a real hustler of Harare streets. At night, he is a tough crime-busting

superhero who straddles this economically distraught nation like a colossus.

Responses (0 )